CLOYINGLY SWEET: Mikayla Brown’s syrupy approach to image distortion and archiving.

Words by Ella Ray

Images by Mikayla Brown and Frances Rich

The URL algorithms programmed to prioritize images deemed profitable and desirable are informed by, and actively informing, our IRL structures. This cycle leaves Black artists creating outside of the framework of representation in fraught, but generative space in the “art world” and online. As social media is further baked into our arts ecologies, the pressure to produce objects and images that are digestible for a broad, white, uninterested audience is at an all time high. As an art historian, and as a Black woman, attempting to evade the canon of my own practice, I am excited by visual artists that decline expectations around creating figural or narrative work-- knowing that this leaves us at an impasse.

Black artists making abstract art are often marked as illegible by institutions that profit from representation politics. And while the obscurity that comes with an abstract, or even experimental, practice is what leads to Black artists like Howardena Pindell and Ed Clark getting their roses decades late, the characterization of illegibility is an opportunity to define the conditions of production and engagement of and with our art.

Mikayla Brown is a Chicago-based interdisciplinary artist exploring interiority through alternative means. Mikayla’s practice is not devoid of identity, but makes distinct connections between materiality and image in ways that reflect an investment in ritual and process. Ironically, I was introduced to their practice via the algorithmically produced “Suggested Follows” feature. Also known as @nectaryear, Mikayla occupies an illusive but notable place on the internet. Their instagram is an assemblage of super-zoomed selfies, dancehall ephemera, and 18 karat herringbone chains. Interspersed throughout are fragments of striking abstract oil paintings and fragile ceramic work. The ebbs and flows of Mikayla’s online-presence, and practice, have left me hungry to know where their work begins and ends.

Through a handful of emails and a long zoom call, Mikayla and I dove into the theoretical and technical underpinnings of their studio practice. Between the moments where we found common ground in our eBay search history and adoration for Fanon, Mikayla gingerly traced the trajectory of their work. Throughout our conversation they wove a complex web of reference and inspiration-- making apparent Mikayla’s commitment to the deep study of art history, popular culture, and image theory.

Growing out of an elementary school hobby, Mikayla recognized that their portrait painting skills could be used to gain access to educational and artistic resources that wouldn’t otherwise be available. The exchange of hypernarrative portraiture for life and practice sustaining funds is not uncommon for Black artists. The benefits of producing art objects that align with a neoliberal understanding of “Black art” is not lost on Mikayla and in many ways, informs their departure from figural work.

“I wasn’t initially drawn to becoming an abstract painter, I actually was really averse to it in the beginning. It was after using painting as a tool to access different resources that I began leaning away from traditional mediums,” explains Mikayla. Experiences with new media technologies, exposure to performance work by artists like Ulysses Jenkins, and a desire to study textures and finishes pointed the artist toward a more abstracted practice. This shift is evident in Mikayla’s cake paintings and “frosting objects.”

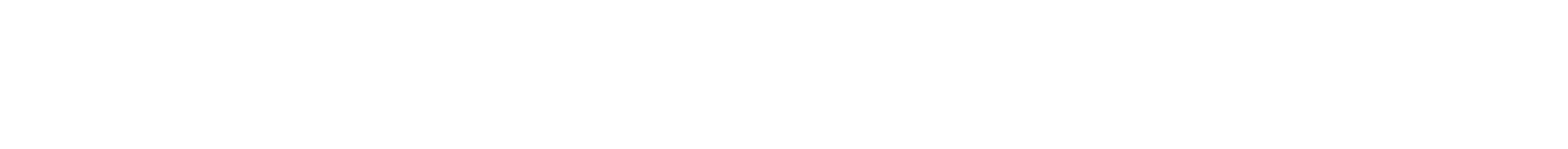

These paintings are often rendered on square canvas and, depending on your perspective, can be understood as a slice of the larger form or as the whole cake. In a swirling palette of beiges, powder pink, neon yellow, and cherry red, Mikayla depicts distorted layers of sponge and globs of frosting. Within a singular painting, the artist’s application of oils range from gentle washes to densely concentrated treatments that reinforce the stickiness of the confection. Placed on the upper ledges of the paintings are the stoneware “frosting objects.” Mikayla pipes these segments out of a pastry bag. After firing, they apply a powder coating that adds a jewelry-like chrome finish that doubly acts as a protective layer. Although these ceramic forms are sometimes exhibited separately from the paintings, the combination of these objects illustrate a tension between deterioration and preservation.

Mikayla notes that they are “usually thinking about how Black people are supposed to present a consumable product, even if it’s an image of something destructive or violent.” While their paintings and ceramic works are hardly violent, these forms serve as material space for the artist to explore the consequences of image commodification over time. These paintings recall desserts at the end of a celebration, where the original object, or cake, is distorted through slicing, plating, and eating. You almost can’t tell if you want another slice or if you’re disgusted by the mess that has been made. In capturing this distortion, Mikayla makes clear the effect of our excessive consumption is an image separated from its origin.

Mikayla’s interest in materiality and image production is continued through their study of jewelry. Informed by working in a Black-owned jewelry shop on the southside of Chicago, Mikayla began documenting the wearable aspects of Black cultural ephemera through a project called “Gilded Cavity.” The archive consists of 58 close-up images of gold pendants, heavy pinky rings, and flat chains. At first blush the Instagram account feels like you’re flipping through a Black family album that isn’t yours, each photo reading as both universal and highly intimate. I saw myself, my lovers, and my kin in the jewelry choices of these strangers. With time though, Mikayla’s selective omittance of the faces and the bodies of the jewelry-wearers brings the formal mixture of metal and flesh to the foreground. The contours of skin begin to mirror the shapes of jewelry and patterns in size, placement, and cut appear repeatedly, giving the archive a scientific quality. Mikayla's powerful play with image structure maps the mundane but tender relationship between metal and Black bodily adornment.

Across their practice, Mikayla Brown is experimenting with maintaining and warping images. While Mikayla’s acute understanding of the rapid circulation of Black cultural production grounds their work, it’s through their sharp exploration of material and process that their practice bears fruit.

Equal parts sweet and sour, decaying and blooming, Mikayla Brown is creating abstract art rooted in the Black tradition of refusal.

ALL Works by Mikayla Brown

frosting (batch c)

stoneware, 2020

the frosting tv

wax, stoneware, silk print, and super8 on 2003 tv, 2020

raspberry cake

oil on canvas, 2020

(Images in couch photo from left to right)

raspberry cake

oil on canvas, 2020

imprint of a pendant with a broken jump ring

oil on canvas, 2020

white t three

oil on canvas, 2020

white t two

oil on canvas, 2020