TRANS ALLEGORIES, ANTHEMS AND THE ARCHIVE: RUSSELL E.L. BUTLER

Words by Esra Canoğullari

Images by Kristin S. Rowe

It was 2016 when dear friend and collaborator Lara Sarkissian and I were walking towards Life Changing Ministries. After parking down a residential street, we walked up to a single story church building moonlit by an unearthly blue glow. We entered into the muffled sound, coming from the DIY music venue in West Oakland to see Russell E.L. Butler and XUXA SANTAMARIA play for the first time. We were consistently going to shows together to look for artists to play at Club Chai, the party we were organizing at the time.

As Russell started playing, we turned to each other and said “Who is this??!” They moved effortlessly through various genres. Even though they were playing off of a PA system and one subwoofer, Russell treated that tiny carpeted church like it was the best soundsystem and dance floor in the city. Lara approached them as they were playing to ask for a track ID.

At that point, I hadn’t seen many DJ sets in the Bay Area that were as exciting to me, to witness someone really pushing what is possible with the craft. What struck me about Russell’s set at LCM that night was their archive, tying so many disparate narratives together. I moved closer to the DJ booth to look at what they were doing.I realized they were playing all vinyl, at the time I felt pretty cynical about all vinyl sets due to the mainly white fetishization of the format. I hadn’t heard a DJ set that vast in a while, Their love for playing records made me rethink my perceived limits of that process. In that moment, they reminded me why I love the potential of records and why collecting and creating our own archives as queer and trans people of color is so important.

I knew I had to talk to them and introduce myself. I didn’t realize until later that our friendship and the dialogues we would have would shape the way I think about sound, my trans identity and the potentials of chosen kinship with both the living and those who have passed.

After our immediate connection, we’d spend hours smoking, talking and DJing in our homes. So much of our friendship is deeply invested in dialogue, critique and uncovering. I’m grateful to witness Russell’s continued understanding of themselves within the history of dance music. The way their specific relationship to Blackness, transness, queerness and diaspora has created a spiritual and ancestral storytelling process that is at the core of their sonic work.

The history of traditional archiving is so much about preventing loss of information or data. What happens when you occupy the parts of the archive that have been disregarded, lost or forgotten all together? The work of uncovering and squinting to see ourselves is a process of longing, grief and transcendence; knowing there's more than what's been offered to us but being given the daunting task to do the searching ourselves. Presenting the histories in our own way and writing it as we live it. Choosing to archive or collect something is in some ways a process of grief— acknowledging the ways you aren’t seen through a decision to create a small universe of your own via the accumulation of objects. To surround yourself in the artifacts of your own universe.

Five years have passed since that night at LCM in Oakland where I saw Russell DJ for the first time. Since then we’ve both left the Bay Area and have moved to New York, our kinship has grown and evolved through one more transition. Our conversations around transness and the way we want to see ourselves have been actualized in some way. We’re sitting together in my room in Brooklyn facing each other next to the same CDJs and mixer we had shared for years in Oakland, sharing a joint, listening to music. Before I started to record our conversation I realized we are doing the same thing we have always done, with the same comfort and ease, years later in a different city and home.

Knowing Russell as a collector of cherished objects and someone who is invested in spirit and ritual, it felt important to contextualize why they’re referred to as a digital archivist, and their recent work with A Song For Frankie. Russell mentions first working in archives alongside their father, who worked as a local historian in Bermuda. One of the most notable archives for them was the book collection that was stored in the den of their maternal Grandmother’s home. In the same room as a desktop computer, was a small library of radical Black literature, where early access to sexuality via the internet, technology and radical Black thinkers happened all in the same space.

Another notable archive was their family’s record collection which had been moved and stored over the years in so many different ways. At one point, they were stacked vertically in the corner of a room. The humidity of Bermuda caused the records to warp, contract, fuse together and unfuse. As they describe these morphing records, I immediately thought about them as living beings—bodies contracting, breathing and reacting to heat. They mentioned the clear and stark gendered difference between their Dad’s records and their Mom’s. Dad gravitates more towards jazz, jazz funk and fusion (Sly and the Family Stone, Donald Bryd, Santana, Jimmy Hendrix) and their Mom’s collection consists mostly of r&b and soul (Roberta Flack, Carol King, Joan Baez).

When I think about Russells’ collection and musical world it's a hybridization of both of these archives and an expansion beyond them. True to their non binary identity, they took their parents' sonic worlds as a point of reference and freaked it. As they discuss the differences between their parents’ collections I laugh as I list off all the artists that Russell loves, that to me embody a true collision of those two worlds: “Alice Coltrane, Ari Lennox, Summer Walker, Future….” We both are listing off artists between laughing. Russell responds: “EXACTLY, EXACTLY, you know—these are all the overlaps. Hard and intense but extremely deep and emotional, watery and mercurial. She’s all there honey.”

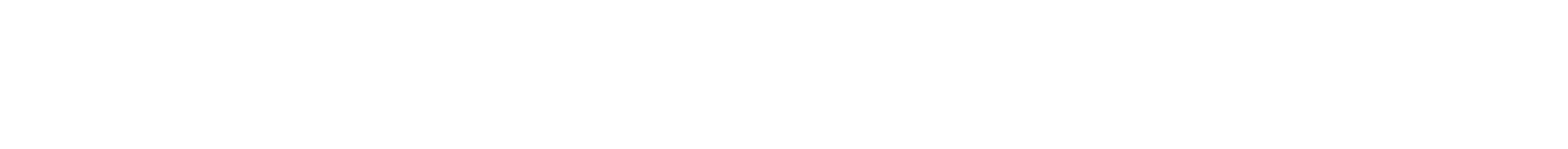

When back home visiting Bermuda after Russell had moved to the US, they were given the task of sorting their family’s record collection if they wanted to keep any of the records otherwise they were going to get tossed. They remember a record that had stuck in their head since childhood and made sure to find their parent’s copy; Caricatures by Donald Byrd,where the cover is a simple black and white line drawing caricature of the musician. Years later upon re-listening to this record they realized that the elements of the music is everything that they look for in a track: “Funky, great arrangement, embraces the synthesizer as a compositional tool and not in a cheesy novel way, jazzy, has improvisation and its a record I still play”.

From June 24 through September 11th, Russell had been working at the Gagosian as a part of Theaster Gates’ piece A Song For Frankie, an installation and one of the artworks included in the larger group show, Social Works curated by Antwaun Sargent. Russell was given the task of playing out and digitizing a large portion of Frankie Knuckles’ record collection in the gallery, seated behind a DJ booth, exposing the process of digitization as a casual repeated ritual for the viewers. When I walked into the Gagosian to visit Russell, the image of our first meeting flashed into my head- they were dancing, sheltered between stacks of their records behind a plywood DJ booth in that carpeted single story church building.

Towards the end of their shift we took a seat in front of the Mariah Carey section of Frankie’s record collection. We start to talk about the way this mass of records in front of us is like a direct extension of Frankie’s physical body and spirit. Russell continues: “I would say that it's not even a body—it’s bodies. Many, many, many, many bodies. And I mean that in the living and the dead sense. Especially within the dead sense.”

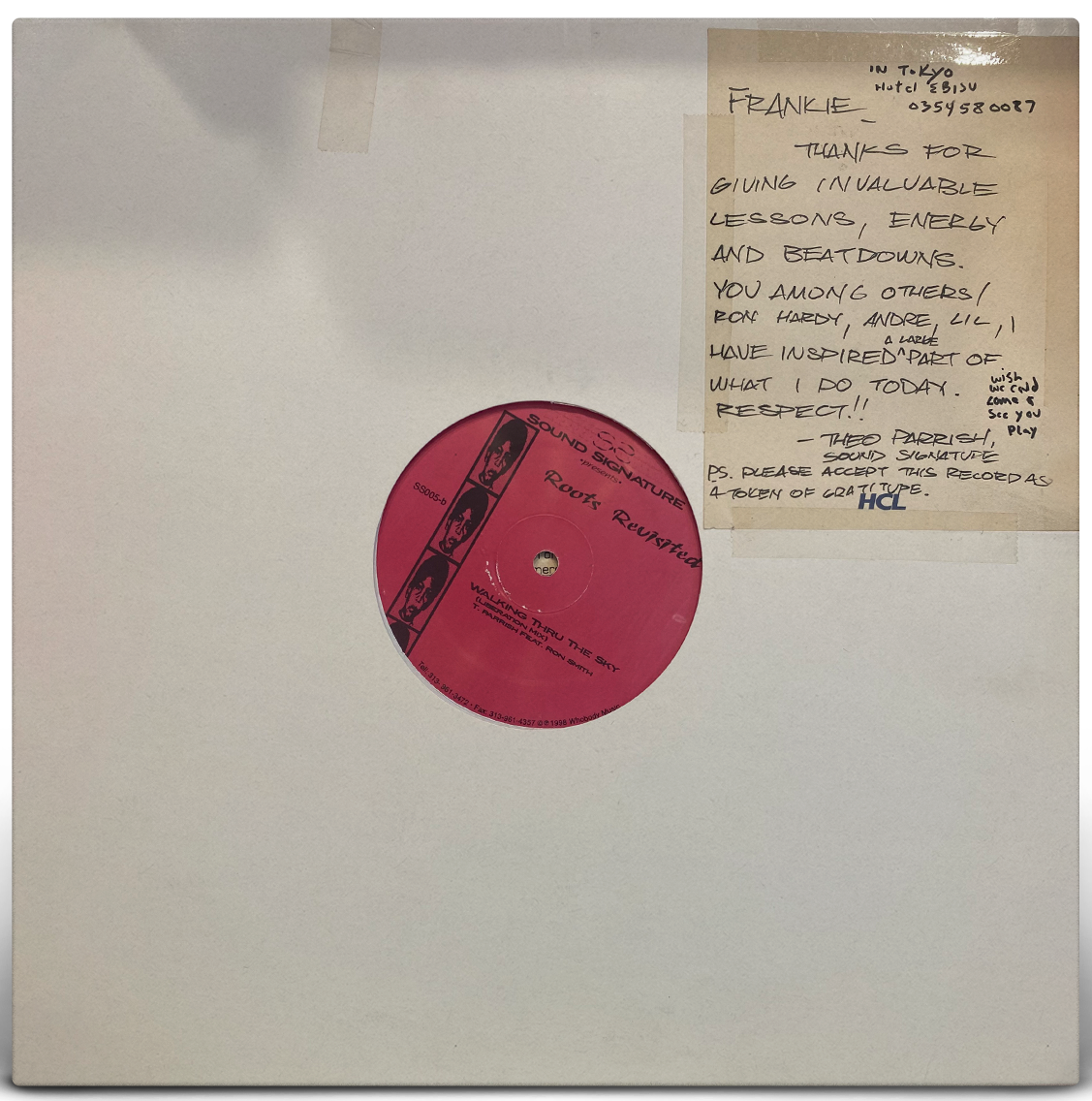

Russell begins to pull out numerous records in the collection with handwritten notes to Frankie on them, expressing their endless love and gratitude. The way people write to Frankie shows their trust and respect for him and the space of feedback, evolution and care that he created for his musical family. One that stood out was the Roots Revisited, a record that Theo Parrish gifted to Frankie:

“FRANKIE, THANKS FOR GIVING INVALUABLE LESSONS, ENERGY AND BEATDOWNS. YOU AMONG OTHERS, RON HARDY, ANDRE, LIL, HAVE INSPIRED A LARGE PART OF WHAT I DO TODAY. RESPECT!! - THEO PARRISH SOUND SIGNATURE

PS. PLEASE ACCEPT THIS RECORD AS A TOKEN OF GRATITUDE (wish I could come and see you play).

Over the period of time that Russell was working with Frankie’s archives I got multiple texts from them saying: “Frankie really showed up for me today.” One of those moments was when they were experiencing transphobic and homophobic violence and harassment on the train and they felt protected by Frankie’s spirit. Another moment was in relation to a musical or creative epiphany. They were developing a direct spiritual relationship with Frankie as kin, as a guide, and an ancestor. I can’t help but think about how the record collection is in so many ways a vessel for that connection to spirit, and how Russell’s daily work with that archive made that spirit move right through them effortlessly.

I saw Russell play at Nowadays after they had wrapped up their work with A Song For Frankie at the Gagosian. I knew after they had emerged from this work this would be an important set. They moved through so many genres, dancing behind the booth lovingly pushing through each song like each one was the peak moment of the set. I was watching them on the rotary mixer and thinking to myself—Russell is playing the way Larry Levan or Frankie Knuckles would play if they were our age and DJs now.

I really felt like Frankie was moving through Russell during that set. I was on the dancefloor thinking to myself I just want to run up and scream to them: “THEY ARE MOVING THROUGH YOU!! THEY ARE MOVING THROUGH YOU!!” but it felt important to leave them uninterrupted at that moment.

Later on in their set they threw on I Want To Leave My Body by Green Velvet. A track we had just talked about the last time I visited them at the gallery and one that I play in lots of my sets. I ran into the booth and hugged them hard immediately and thanked them for playing it. After dancing with them behind the booth I looked up at the ceiling, at the pink smoky haze and refracted disco ball lights that became immersed in my tears. Through the soundsystem and through this song I remembered the power of queer and trans kin, of chosen ancestors both living and passed.

When I first heard ‘I Want To Leave My Body’ I felt so heard and seen as a trans person- the idea of wanting to leave my body and float away into space. Something about this track felt so affirming to my gender experience and dysphoria while also being transcendent and euphoric. Making the fantasy of wanting to leave my body feel affirming and expansive. Maybe it’s not about leaving my body but moving beyond my body? That’s what the speakers are for- remembering what it’s like to be beyond a body—to collide with space, time and memory.

Russell explains how being seen by someone’s music for the first time can feel like a stranger is reaching into your brain and plucking something out and presenting it in front of everyone:

“The experience of listening to something and being like—YOU KNOW ME. YOU KNOW my LIFE. YOU DON’T EVEN KNOW I FUCKING EXIST BUT YOU. KNOW. ME. Sometimes that hypervisibility can feel terrifying, it's like a spiritual outing.”

I mention Transition by Underground Resistance, a track that has lived in Russell’s DJ sets for as long as I've known them. They explain how Transition is “within the spiritual channel, you can’t exactly put the experience into words but you know where it comes from and your place in it regardless of whether or not the creators understand or know that personal meaning”.

“Transition is a track is that so many people can relate to- if you talk to anyone who has a really intensive experience of pain that is transformative, which one could also argue is the experience of being transgender—the constant reconciling with the body as it is presented and perceived within western white supremacist patriarchal capitalistic society and trying to still build it and survive within that context and then finding something that is so affirming and transformative.”

Russell’s practice is always orbiting around the spiritual channel. Creating while acknowledging that place, hoping to be there, sometimes being immersed in it and other times reaching towards it. That feeling of forward momentum and push within the channel is the transformative part. Then there’s the process of looking back, to know and understand what this experience is. To be able to take advantage of it and allow yourself to be transformed.

“To have your molecular structure changed. To bring it back to the archive, the more you have to pull from, the deeper those transformative experiences can be.”

Russell E.L. Butler recently released an EP ‘Collective Response to Giving Up’ and will be starting a Europe tour at the end of November, keep an eye on their socials for dates and announcements.